Motherhood, Translingualism, and the Borders: A Conversation with Natalie Scenters-Zapico

by Ariana Matondo

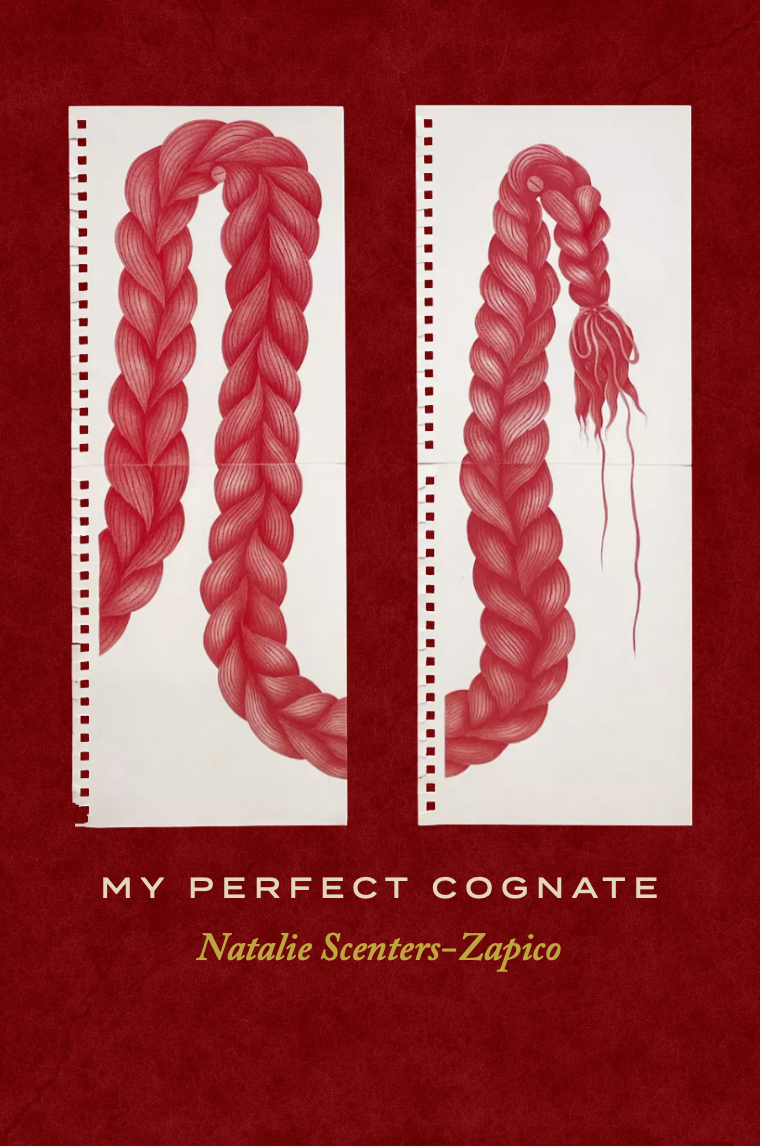

This September, critically acclaimed poet Natalie Scenters-Zapico published her newest collection titled My Perfect Cognate, published by Copper Canyon Press. This will be her third book, following Lima :: Limón (2019) and The Verging Cities (2015). I had the incredible opportunity of introducing Scenters-Zapico at her reading at the University of South Florida, sponsored by their Humanities Institute’s Garry Fleming series. My Perfect Cognate interrogates this question: How does one navigate the world when caught in-between two cultures, two languages, two different ways of being?

The cognate is not just a linguistic craft concept in this book. I once explained My Perfect Cognate to a non-poet friend using this analogy: Scenters-Zapico is wearing words as if she were combing through a closet, trying on different outfits. In my analogy, the cognate is the outfit. It’s not just a definition—it’s a persona, a metaphor for lineage, and a traveling between two different cultures. The second poem in the book, Falso Cognato, opens up with the line: “Language is a mirror I never tire of looking into”. This sentence begins the foray into experimental work with translation that Scenters-Zapico does throughout the book. This is also done with the definition of the agnate, which is a relative connected through patrilineage.

Throughout the collection, there are themes on the complexities of motherhood, post-partum depression, medical malpractice and mistreatment of women, as well as the interweaving of legislation and lived experience.

The following is an interview conducted with Scenters-Zapico, where we discuss the aforementioned themes, as well as craft elements, form, and the writing process that led to the creation of My Perfect Cognate.

ARIANA MATONDO: Throughout the collection, the image of the cognate reveals a truth about how the English language is elevated in western society, while Spanish is not. You depict this polarity in the poem In Cognate, describing it as “...the order of letters that renders / the mule deer standing in the desert / from the excavator clearing the desert”. Later in the poem, the layers of dichotomy peel back further: “… The cognate is no citizen, / but a cognate will split the land & taint it / black with bollards tall as the letters / in the congressional bill it calls home”. How did you come to this idea of using the cognate as an anchor between English and Spanish in the collection? What was the process like turning the cognate into an image the reader can grasp onto?

NATALIE SCENTERS-ZAPICO: A month after having my son, my mother was diagnosed with breast cancer and had to go through chemo and radiation. I fell into a severe post-partum depression that consumed me completely. I felt incapable of having a conversation, let alone express how or what I was feeling to anyone, even a therapist. I felt completely muted by my new motherhood, and more animal than I ever had before. I was all function and service and couldn’t lean on my mother to help me see my personhood again. I kept trying to write and talk in any language that I could, Spanish or English, and both seemed totally insufficient. I wanted to be without language, but I also wanted to be understood—something I wrestle with throughout the collection. So, I started to think through the metaphor of the cognate. Words that on the one hand we rely on to absorb meaning reliably, but on the other are trickster figures that can mean something entirely different than what we intended. Cognate also refers to tracing one’s lineage through the mother, something I felt very attuned to after having my son and realizing just how much mothers (whether birth mothers or not) give of our physical bodies in caring for babies. So, like many writers before me, I tried to take an abstract concept like the cognate and bring it down to the physical plane. How is my relationship with my bilingualism in English and Spanish affected by the fact that they are both languages of empire and colonialism? How does English function as a neo-colonial force in my life in the context of a Trump presidency? Is it perhaps a tall order to ask that a reader have an emotional connection to something so abstract like the cognate? Perhaps. But I also know that for the code-switching bilingual reader they already function in this intellectually vigorous mode all the time. I was interested in exploring how the code-switch serves as more than just a way to show cultural understanding and emotional nuance but also be a formal device.

AM: Continuing the conversation of cognates in your collection, how did you make the decision on what Spanish words to weave into the English translations, and what English words to weave into the Spanish translations? Some of them are cognates, but some are not (like in En Cognato, with the word ‘jefa’/’boss’). Would you say it took a lot of trial and error with picking the words to emphasize in the translations?

NSZ: It was so much trial and error! At first, I wrote the poems with transparent rules: all must be cognates in the “En Cognato” poems for example. But then there were words that I knew would translate to the bilingual speaker from the border despite fluency level, like jefa. Is that not also then a kind of a cognate if it’s understood across cultures and countries by all the people of a certain region? Instead of shying away from that kind of multiplicity in understanding I decided to use it to my advantage and play further. So, I did this in both the Spanish and English dominant versions of the poems. All of the “En Cognato” and “Falso Cognato” poems can be read for different meanings across languages and “errors” in those languages.

AM: What was the process like when you translated your own poetry from Spanish to English, and vice versa?

NSZ: It was difficult because writers are notoriously bad translators of their own work. If I thought of these as purely literary translations I probably wouldn’t have done it. But instead, I thought of them as inverse mirror reflections of each other. How could one version reveal something about the other and vice-versa? How, like children, do they reveal something about their mother (me as the poet) though they speak different languages entirely? How are the cognates both moments of recognition and moments of distortion? How can these ideas be played with by breaking both languages apart?

AM: Were there any books you were reading while writing My Perfect Cognate that inspired you or spurred you on? What about other forms of creative media (eg. music, films, etc)?

NSZ: I spent a lot of time with Sharon Olds, Jaime Sabines, Alejandra Pizarnik, Marosa DiGiorgio, and Juana Ibarbourou, to name a few. I also re-read Ariel [by Sylvia Plath] for the first time since my early twenties, and the ways Plath writes about motherhood and personhood hit differently for me this time. I worked a lot with Susan Briante’s Defacing the Monument, Iliana Rocha’s The Many Deaths of Inocencio Rodriguez, Ronald Rael’s Borderwall as Architecture, Nicole Sealy’s Ferguson Report, and Kim Hyesoon’s Autobiography of Death, to name a few. Books stayed with me longer than other forms of media while working on this collection.

The strange thing about the media (not literary) that I consumed during this time is that I was in such a trance, either from pregnancy or surviving that first year, that I hardly remember it. It was like it all just washed over me because I was in such physical and emotional pain. Nothing was curated; everything was about survival. For my last two books I could give you very specific, beautifully curated lists. But for this book, to tell you the truth, what I remember is the visceral sound of my breast pump whirring in the background, the smell of cleaning all the parts in the sink over and over again, burning myself with the sterilizer. I was also scrupulous about keeping a feeding and diapering journal in those first four months, which turned into its own kind of poem journal.

AM: What was it like incorporating research into your poetry while still making it personal to your lived experiences (like in H.R 7059 In Cognates)? Every nod towards the current political climate in this collection reveals an emotional truth at the same time. A striking example that comes to mind is in Baby Blues, where the baby son's teeth in the poem are described as ‘Epstein pearls’. In this way, you are able to evoke images that both surprise and disarm the reader, since we’re not always expecting it. Although the two are inherently intertwined, how were you able to strike the balance between the political and the personal in this way?

NSZ: This is a question I get a lot throughout my three books. I’ve never sat down to write a political poem. There are wonderful poets who do this, it’s just not something that I’ve ever sat down to do. Instead, when I write I’m constantly revealing to myself and my readers all the ways that politics affects my physical body and the bodies of those I love. All my life where I go, who I love, how/if I give birth have been dictated by the U.S. government. Some are just realizing this since the Trump presidency, but as someone who grew up on the border, I’ve seen the ways in which this has been done incrementally for decades. Borders truly are test tubes for globalization. What happens there has and will spread to the rest of the country. To my mind, the political is never not personal. You just might not always be the person directly affected by a certain politic.

As far as incorporating research into my poems, I think that I’m just a voracious reader. If I could read for a living I would. I love the book object, the chapbook, the broadside, the ephemera of physical writing. I’m director of the Michael Kuperman Memorial Poetry Library at the University of South Florida, so I’m lucky to be able to immerse myself in books all the time. And then, of course, it’s only natural that what I read shows up in my poems in some way. And then, there’s the research of living a life which is vital to a poet. I live and I observe, and I read and then I write to try to make sense of it all.

AM: The first line in Falso Cognato opens up with: “Language is a mirror I never tire of looking into”. This is evident throughout the entire collection, but I particularly want to focus on the first section, which uses the words ‘cognate’ and ‘agnate’ to interrogate matriarchal / patriarchal lineage, as well as the Oxford definition(s) of those words. Could you share a little more how you came to this idea of using these words and interrogating their definitions in layered, multi-faceted ways?

NSZ: I’ve always had a love-hate relationship with the OED. On the one hand, I love language and so I love the history of language and linguistics. On the other hand, the OED is a colonizing force that tries to capture the changes in language while prizing English above all else. The OED is especially tricky because unlike the Real Academia Española, which is very concerned with maintaining a kind of “uncorrupted” Spanish, the OED pretends to be more progressive adding current trendy terms to its pages to show that they are accepting. But really, in my view, this is just a way of erasing other people’s languages and cultures and claiming them as English, as assimilated, as part of the monolingual, monoculture. I love having little arguments with the OED, so I thought what would it look like to document that argument in the very form of an OED entry? This is how the OED poems came to be. Every time I had a hard time writing, I’d think: let’s pick a little fight with the OED today.

AM: The intersection of motherhood, illness, and mental health comes up often in this collection. What was it like establishing a metaphorical landscape for something so deeply personal? What advice could you give to emerging poets who seek to write about trauma without retraumatizing themselves?

NSZ: Developing metaphorical landscapes is really the bulk of what I do as a poet. I often draft purely in metaphor and then have to go in during revision and see what it is that I’m actually talking about. What is it that the psyche is trying to reveal to me? Then it becomes about sculpting a balance between the metaphor and the literal for me.

To emerging poets, I’ll tell you what I tell my students. You can have a wonderful writing day, a day full of progress and leaps, and the creation of an exciting draft. That very same day can also be a terrible personal day, a day full of anxious processing and pain. I try to reckon with the fact that this is part of writing poems and later turning those poems into a book. This is why having other writing side projects is so important to my practice. I’m always working on a translation of someone else’s work, building the Kuperman Poetry Library, and engaging in other’s work in any way that I can. This helps me to lead a more balanced life. Yes, as a poet your life should be about the poems, but it also takes an entire ecosystem to sustain this over a career so I’m always trying to help that ecosystem.

AM: My last question has to do with the image of mirrors, which are used to break up the sections, as well as reflect (no pun intended) the self-image of the speaker, among other things. The nature of this collection plays with the etymology of words and manipulating language to glean different emotions and cultural observations. That being said, how did you settle on the image of the mirror to do the work of revealing the interiority of the speaker? What was the revision process like in narrowing down ways to do this without sounding cliche or repetitive?

NSZ: I don’t know that I ever settled on the mirror image, so much as it picked me. I kept writing about mirrors in weird ways and mirrors kept coming up in my reading. Or maybe poems with mirrors kept finding me? Either way, after having my son I had a terrible time looking at myself in the mirror. My body had changed tremendously, and I found myself so aged in the span of that first year I hardly recognized myself. I still struggle with a kind of body dysmorphia that often makes me wish I didn’t have a body or wonder what it would be like to escape the body entirely. I also suffer from endometriosis, so I feel like I’m always swollen or distended in some way. I found myself hating mirrors in my day-to-day life but obsessed with them in my writing. I just kept working the image in the poems and then across the collection so that each time they appeared they felt different and aided in the larger themes of what I was trying to say.